My first summer working in a kitchen was like acquiring a secret identity. I shook everyone’s hand and said “Hi, I’m Andrew Bates,” nervous and trying not to embarrass my cool friend who already worked there. Almost certainly, within an hour each line cook said “Who’s that green-gilled teenager in the dish pit?” and checked the schedule, where the kitchen manager had scrawled my name as “ANDY” with a permanent marker, so Andy I became.

The cooks cussed and joked and teased each other, drank powdered Gatorade out of squeeze bottles and sang. With our outfit of black jackets with the restaurant’s skull and crossbones logo, checkered pants and bandannas, we felt like pirates. I turned 19 — literally came of age — in that kitchen, and the people I met both on the line and after hours, at the restaurant’s bar and every other bar on the waterfront, taught me how to drink and eat well. I was in awe.

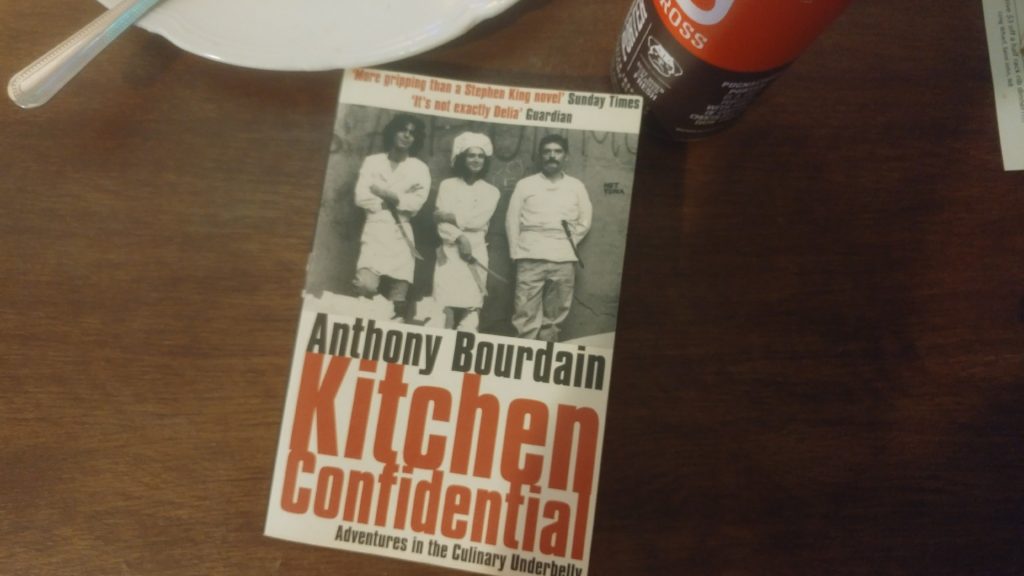

When the ride came to a stop at the end of August and it was time for me to go to college and be Andrew again, it felt like I’d hung up my cape. I cracked open Kitchen Confidential by Anthony Bourdain — which I had first seen in the bathroom while drinking at a cook’s apartment — and his lucid, daring, coarse description of starting in Provincetown, going to culinary school and alternately making it in New York, cemented what had entranced me about that life, and confirmed that that summer wasn’t a dream. But it also set the bar for what the profession’s highest levels were like, how much determination was required, the pitfalls that could lead someone to self-destruct and what it took to come back after. The weird, nocturnal culinary underworld and its detachment from ordinary life was seductive, but I also saw the cautionary tale.

Bourdain wrote about the experience of being a chef as an all-encompassing experience, waking up and lying in bed, “in the pitch black for a while, smoking, the day’s prep list already coming together in my head.” I loved the kitchen, but it ended up that I had that kind of devotion for journalism instead, a world where my secret identity and my daylight one became one again. But the kitchen stays with me, long after I stopped working in it, and the lust for life that I saw there and which Bourdain showed the world in his books and shows is a key part of who I am.

I saw that he died of suicide this morning the first thing this morning, lying in the dark and opening my phone to flick through Twitter and the day’s news. That he took his own life was shocking given how well he lived it. When the wrestling and boxing commentator Mauro Ranallo’s new biographical documentary, Bipolar Rock N’ Roller, premiered in Toronto last month, he told the crowd that the film’s purpose was to spread awareness of the impacts of mental health issues, because we’re losing people. “There is so much stigma, still,” he said. “I ask, I implore, I beg you, not one more. Men, especially … we are all in a fight, but we are losing the battle” because of the invisible nature of mental illness.

Bourdain often wrote, as recently as an interview with Air Canada’s in-flight magazine this month, as a man incredulous that he had made it this far at all. “When they’re yanking a fender out of my chest cavity, I will decidedly not be regretting missed opportunities for a good time. My regrets will be more along the lines of people hurt, people let down, assets wasted and advantages squandered,” he wrote in 2000, before true fame. “I’m still here. And I’m surprised by that. Every day.”

I read that quote while looking for a lasting image from Kitchen Confidential that sticks with me to this day. It’s after Bourdain rebuilt his life, on a trip to Japan as the chef of Les Halles to help its Tokyo location establish itself. Between slurping soba, trying not to step on toes and barely sleeping, Bourdain tells the story of an incredible meal in a Roppongi restaurant tucked away and down a nondescript staircase.

“We went on, calling for more, our appetites beginning to attract notice from the other chefs and some of the customers who’d never it seemed, seen anyone — especially Westerners — with our kind of appetites. Each time the chef put another item down in front of us, I detected almost a dare, as if he didn’t expect us to like what he was giving us, as if any time now he’d find something too much for our barbarian tastes and crude, unsophisticated palates. No way. We went on. Calling for more, more. Philippe telling the chef, in halting Japanese, that we were ready for anything he had — we wanted his choice, give us your best shot, motherfucker … our hosts, the chef joined by an assistant now, seemed impressed with our zeal, the blissed-out looks on our faces, our endless capacity for more, more, more…

“After course twenty or so, the chef slit, brushed, dabbed and formed the final course: a piece of raw sea eel. Earthenware cups of green tea were delivered. Finally, we were done. We left to the usual bows and screams of ‘arigato gozaimashiTAAA!!!’ and picked our way carefully, very carefully, up the stairs, back to the physical world.”

I’ve felt that feeling of sublime satisfaction while staggering into the night, a gentle release from an experience that engaged my whole being, in the streets outside of kitchens, newspaper offices, lovers’ apartments, soccer stadiums, the cab from the airport, movie theatres and a thousand other places. I still chase that feeling, of being alive.