Comic books fight between themselves and their own legends.

Several times a month, comics try and tell new stories in Gotham City, but there’s a lot they can’t change. In the words of Grant Morrison, “Batman always must be Bruce Wayne, in his mid-30s or late 30s, and he always must have a Batmobile and a butler.” It’s a comic book, but also a cartoon and also a lunch box. Sometimes, that can seem negative. It means that we can’t have the Ryan Choi Atom, and why after almost 20 years of being dead, Barry Allen is the star of the Flash book. If the solicits are any indication, it’s why Dick Grayson won’t get more than a year to be The Batman.

But sometimes, it’s positive. Some of the greatest Batman stories are almost impossible to tell in one go as a movie. A story about Oracle must first deal with Batgirl and The Killing Joke. Can you imagine trying to tell a story about Dick Grayson’s life? Robin, Teen Titans, Nightwing, Battle for the Cowl, Batman, and whatever will come next. This brings us to the story of Jason Todd. Not only is his story spread out over 20 years, but its continuity is tied to some of the more annoying pieces of DC storytelling, with two universal retcons and a 1-900-number choose-your-ending story. Batman: Under The Red Hood picks the best story elements and combines them with what we know to tell a gripping and famous Batman story in one shot.

Comics, everybody

I mean, let’s take a look at the source material for Under the Red Hood. Jason Todd was introduced as the new Robin in 1983 after Dick Grayson moved on from Batman stories to lead the Teen Titans, eventually becoming his own superhero called Nightwing. Well-meaning, Todd was essentially a Grayson clone who was also a circus acrobat and also had his parents killed before Batman took him in.

Then, in 1985, the Crisis on Infinite Earths combined all of the worlds of DC’s multiverse into one, allowing writers an excuse to make wholesale changes to backstories. Jason Todd became a streetwise orphan who met Batman when he tried to steal the tires off of the Batmobile. He was Batman’s attempt to keep a child from joining the “criminal element”, and he was mouthy, brutal, and occasionally incompetent.

This leads to 1988. Todd had been unpopular, and DC Comics had been looking for a significant enough story to introduce a plan to allow readers to determine the outcome by voting via a 1-900 number. Enter Death in the Family. At a particularly low point in the Todd-Batman relationship, Jason discovers information that could lead him to his birth mother, and steals the Wayne credit cards so he can fly over to the Middle East.

He (and Batman, who was in the country chasing the Joker, but letting Todd run away) finds his mother being blackmailed by the Clown Prince. As Batman goes one way to catch the main criminals, Robin goes the other way to rescue his mother — who has ratted him out. Trap sprung, the Joker beats Jason half to death with a crowbar, and then explodes the building. By a total of 5,343 votes to 5,271, Todd is found dead by Batman.

And that’s it. Batman tries to kill the Joker, who, bafflingly, has been made the Iranian ambassador to the U.N., but is forced settles for his helicopter crashing into the river.

And then, for fifteen years, in a world where so many others came back, Jason Todd stayed dead. Batman’s failure to save Jason became a driving part of his character almost rivalling the death of Bruce’s parents. A memorial bearing his costume is seen as one of the lasting fixtures in the Batcave, and the issue was brought up often whenever he faced the Joker, although he could never let himself sink to the Joker’s level and kill him.

But even the “deadest characters in comics” can come back. In 2002, the Hush storyline introduced a new villain, someone from Batman’s past that used detailed knowledge of Bruce against him. Several teases that this would be Jason Todd lead to a creepy, excellent graveyard fight between Bats and an older, meaner Jason. But he turned out to be a Clayface clone — another way to strike at Bruce’s weaknesses.

The door was left open, though, and sure enough, in 2005, the Under the Hood storyline introduced a vigilante named the Red Hood who ran his own, no-kids crime racket and killed dirtier gangsters. Hints that this character was Jason Todd were at their greatest where a science-minded Bats tracked down Green Arrow and Superman, asking them what it was like when they died.

The explanation for the resurrection? Before 2005’s Infinite Crisis, Superboy-Prime punched reality, splitting one world back into the multiverse, and, specifically, beaming a copy of Jason Todd from an alternate universe where he survived the explosion into his own grave. Jason was then taken in by Talia al Ghul, healed in a Lazarus Pit, was around for the first half of the fight in the Hush story, and then tagged out for the Clayface clone and bided his time. It’s also full of references to the ongoing Infinite Crisis storylines of the time — Batman and the Leaguers are on bad terms because of the events of Identity Crisis, and Deathstroke tries to recruit the Black Mask into the Secret Society of Super-Villains.

To sum up by stealing a riff off of Let’s Be Friends Again, the second Robin was turned into a douchebag when the multiverse was compressed, and was voted out of life. A version of Jason from a universe where fans voted yes was transported into the story when Superboy-Prime punched reality so hard it broke. He then grew up behind the scenes and is now a dangerous brutal crime fighter that kills everyone. Comics, everybody!

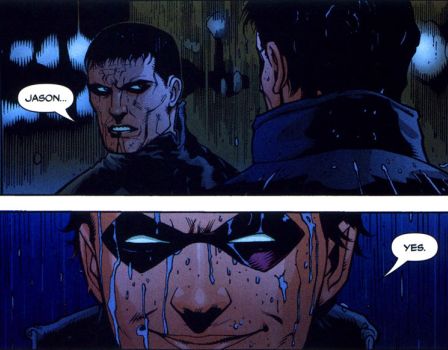

Do you know what I miss most about running with you?

Under The Red Hood takes these disparate story elements and manages to knit them into one clear film by painting the story in its broad strokes. After all, this story isn’t about punching reality or 1-900 numbers or even bringing back the deadest character in comics. This is a story about forgotten things coming back, of Batman facing his biggest failure — and his past.

The movie opens with the Joker beating Todd with a crowbar in a scene that declares the film’s darker subject, covering all of the important parts of Death In The Family in almost ten minutes, leaving out references to Jason’s mom or the fight at the U.N. What follows is a gripping, character driven story liberated by the trappings of its comic book context.

When Batman’s breaking his first Red Hood crime, he gets bailed out of a fight with Amazo by Nightwing, who Exposition Thug helpfully explains is the first Robin. Batman leaves without explanation to continue the investigation and later sends Dick home, insisting that he doesn’t need his help. He’s just not comfortable with having a partner, after Jason, and while the two can work together, Nightwing always feels a little bit out of the loop.

The chase takes Batman to another uncomfortable location for his first face-to-face meeting with the Hood: Ace Chemical Factory, where years before, the first Red Hood, an unconfident, incompetent thug, trips over his own cape while backing away from Bats and falls into a chemical vat, causing him to become the Joker. This scene shows the secret of the film’s great action scenes — things explode and Batman has to swing around on ropes a lot, but the actual result of the fight is not important — it’s a chance for the Hood to take a chance to take Batman down Memory Lane to remind him of his failures.

The next stop is to go back to see old enemies. “But he is locked up.” Nightwing says, half a question, about the Joker. “Like, a lot locked up.” John DiMaggio’s excellent rendition of the Joker pays homage to the Mark Hamil interpretation in the animated series without being indebted to it. It also proves that there are new ways to look at the character post-Heath Ledger; that his version, though popular, can contribute to new ways of looking at the Joker without overshadowing them. The Joker takes the opportunity to not just remind Batman that he killed Jason Todd, but that Batman can’t bring himself to kill him over it.

Some of the best parts of the film are the scenes involving young Jason Todd. As a child, he’s full of verve and enthusiasm. As an older adult, Todd shows his slide into use of excessive force. The flashbacks are all transitioned in with fades that show the characters first as ghosts inhabiting old settings.

The interplay between Bats and Todd is also very interesting — they team up to fight a ninja group known as the Fearsome Hand of Four (thanks to the creators for using original characters, rather than the comics’ cringeworthy Captain Nazi and the Hyena). Their interplay shows what makes Jason Todd such a good adversary for Batman — he’s so familiar, which puts Batman off of his game. Bruce doesn’t like to be reminded of the fact that the crime lord/crime fighter he’s fighting beside used to be Robin, because he is so not over it.

And that interplay is what drives the story. The Black Mask, captured in all his madcap brilliance by Wade Williams, realizes eventually that this story isn’t about him at all, that he’s just caught in the crossfire. Indeed, it’s all summed up in a climatic scene between Batman, the Joker, and the Red Hood in an apartment on Crime Alley, a location with so much history for three people with so much history.

Bruce, I forgive you for not saving me.

In the end, Under the Red Hood tells the 20-year long story of Jason Todd in a brisk 75 minutes by stripping the story to its basics. The resurrection is explained as Ra’s al Ghul trying to make amends for hiring the Joker all those years ago when Jason died by using a Lazarus Pit.

In the comics, all of the Pits have been destroyed and Todd was too far gone to use them anyways, but we don’t care. We know about Lazarus Pits, and we know about al Ghul, so he doesn’t even need to be explained.

The backstory for the Joker used is the one from the Killing Joke, but it doesn’t need to be explained because we’re familiar enough with it. There’s no Deathstroke, no lame team of Society castoffs for Batman and the Red Hood to fight, and no Chemo exploding over Bludhaven, but the story doesn’t suffer without them.

But at the same time, this story doesn’t sacrifice the source materials. Settings are authentically reproduced, and many scenes, especially the big confrontation at the end, are word-for-word accurate to the book. The costume Bats wears in his flashbacks is the Neal Adams number with the oval logo, although the older Jason’s uniform is more like Tim Drake’s green-less number.

Amazo appears, with his character an implicit reference to the Justice league. Talia appears and is never named. A throwaway line in the climax makes reference to that other thing that happened in the Killing Joke — the crippling of Barbara Gordon. This is still a universe in which all these things happened.

Legends sometimes trap narratives in their wake. But they can also help free them from the trappings of continuity that can hold them down. In the heartbreaking final scene, a tired, older Batman remembers a younger, happier version of himself with a carefree young Robin II. The image is so effective and so sad because it is now tied to what he will become. These characters are are legends, and now so is Jason Todd.