Our frustrating national debate on minority governments will not be solved until we settle who wins a general election and, more importantly, what mandate that gives to governments.

Right up until the MOMENTUMQUAKE hit today, the week’s big political topic was the resurfacing of the coalition debate, but with some substance, this time! On Tuesday, Ignatieff confirmed in an interview with Peter Mansbridge that the Liberals could lead a government between elections if a Tory minority lost confidence. National Post columnist John Ivison wondered aloud whether or not they teach “Don’t answer hypotheticals” in MP school, and the right wing lost their shit over Ignatieff’s “lust for power”. On Wednesday, Harper didn’t exactly cover himself in glory either, as he refused to confirm that he’d work with the opposition in a minority, but boldly told Peter Mansbridge today that he wouldn’t try and lead a minority parliament as the second place party between elections despite the fact that he did that exact thing when the 2004 Martin minority was on the rocks. Still with me? Good.

What all this proves is that there is a serious disconnect between what some people think the system means and what it actually means. Democracies are either direct, where your vote makes a specific decision, or representative, where your vote selects someone to decide a whole mess of things on behalf of you and everyone in your area. Voting for an American president is an act of direct democracy (kind of! we’ll get to that in a bit), while voting for a Parliament is a representative one. In both models, everyone you elect is supposed to represent everyone–a President and an MP is everyone’s politician, not just the people who elected them. At the local level, the election is simple. The MP with the most votes wins. Even if more than 50% of votes were cast for other candidates, those other votes are discarded, as if they were goals scored by the losing side in a cup final. The most representative MP then goes to join 307 other MPs to run the country in Ottawa. What gets murky is when you add political parties.

Political parties are private membership based societies that are a useful tool to group political will. Without them, as it was in BC until 1903, parliaments were governed by loose coalitions that, in BC, saw Premiers turfed by the Lieutenant-Governor often, with sixteen premiers serving in a period of ten elections. The problem is that elections have nothing to do with parties. Theoretically, your vote for a political party’s candidate for MP means that you would support that party’s leader as the Prime Minister. But Canadians never vote for a Government. The Prime Minister’s Office isn’t even in our constitution–there are no rules, only formal conventions about what constitutes the Queen-in-council. Eugene Forsey tells me that by convention–which is oddly enough enforceable, because Canada is weird–Parliament selects a candidate for PM, who names a Cabinet to run the government and formally advise the Queen how to exercise executive power.

So who wins an election? Unlike a race for MP, the game doesn’t end and the votes mostly don’t vanish. But the unofficial rules surrounding how a political party controls democratic power ends up in weird solidifications of that power. Just after starting a brief hiatus from public life in 1997, Harper once told an American conference that the House of Commons was more like the US Electoral College than Congress; “Imagine if the electoral college which selects your president once every four years were to continue sitting in Washington for the next four years.” The Electoral College is a weird construction–in order to weight population density in presidential voting, Americans elect token representatives that meet after an election to vote for the President and then disperse. The thing is, if Harper thinks the House works like the Electoral College, it would make sense how he feels about winners and losers, because in that system, the votes DO disappear. The candidate with the most votes forms an executive council, everyone else goes home, and the apparatus for representative democracy is a completely different election altogether. But we don’t work like that at all.

Still with me? We elect MPs to represent us in Parliament. Parliament endorses a Prime Minister, whose Cabinet is, unlike the American system, answerable to the legislature. This is called responsible parliament, which sounds loaded, but really, it just means what it says–government must have the support of the house. That responsible thing is what throws everything off. Because in practice, the Parliament votes on party lines. Parties hire Whips to ensure party MPs vote with their leaders, and crossing the line outside of a vote your leader hasn’t declared a free-for-all means you usually get thrown out of the caucus, which makes it hard to get re-elected.

So who wins in a federal election? Without any rules, everyone agrees that the party with a majority–50%+1–of seats gets to form the government. With 155 or more MPs whipped to vote along party lines, Parliament will approve most of what the political party who forms government does because that party controls Parliament. But no party has had a majority in Parliament since 2004–a whopping four elections ago. (If you’re keeping an unnecessary-election score, two of those were called by Prime Ministers and two were the result of votes of non-confidence moved by the Leader of the Opposition; Stephen Harper two, Ignatieff one, Paul Martin one.) The rules of what happen in a minority government are clear, but how that relates to an election starts to get confusing.

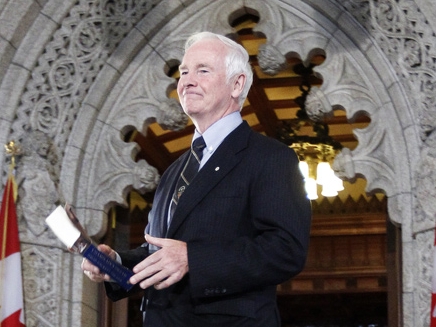

By convention, after an election, whoever was the prime minister is still the prime minister. If they lose, they resign. Then, the GG approaches the leader of the party with the most seats and asks them to have a go at forming government. Government rules until they lose the confidence of parliament–a throne speech, budget, or any other confidence motion fails–and the Prime Minister goes back to the GG and asks them to dissolve Parliament and call an election. Usually, the GG says yes. We so rarely ever get past this point that it makes sense that nobody remembers how it works. The GG has the rare power to refuse advice from the PM in this case–since his job is to make Parliament run after an election, a GG could refuse to dissolve it under the rationale that another election would not be in the best interests of Canadians. If that happened, as it has happened before, the current GG, David Johnston, would summon the Leader of the Opposition, tasked with maintaining a government-in-waiting, to ask if he thought he could form a government that has the confidence of the House. Things like the 2008 coalition agreement, Harper’s 2004 letter to Adrienne Clarkson, and Bob Rae’s 1985 deal with the Ontario Liberals are really just props designed to prove to the GG at this point that they could form stable government. If Johnston was convinced, that party would get to form a Cabinet and make a Throne Speech. If Johnston wasn’t convinced, or the Leader of the Opposition said no, he’d go to the next party and so on, trying to encourage Parliament to work together for about six months before he got tired of it and would call an election already. Examples of this system at work include the last British election, where Gordon Brown placed second, but as Prime Minister, was given the first shot by the Queen at forming a government with confidence–which failed, because his opposition said no–and a coalition of David Cameron and Nick Clegg accepted the call to form a government.

Who wins in a federal election when no party gets a minority? Brad Wall thinks it’s the party with the most seats: winners WIN. But without rules, what’s democratically correct is left ridiculously subjective. Is a government legitimate if less than half of Parliament supports it? Is the government with the support of the most MPs automatically the most legitimate? This is when political parties become a pain in the ass. Since political parties are viewed as Team Layton, Team Ignatieff, etcetera, majority thinkers like Wall and Harper see the seat counts as a score card, and whoever won the most seats wins the Legitimacy-to-Govern trophy. And while it usually does, the fact of a minority government–and arguably, its mandate–is that the government cannot continue without the support of other MPs. Whereas in a majority, the onus is on the opposition to work with the government, in a minority, it is the government’s responsibility to seek the support of the opposition, not the other way around.

So why are we even having this argument? Simply, the political scenesters–politicians, strategists, pundits, reporters–have already decided this scenario is going to come to pass. Pollsters mostly predict that the status quo will hold for the second straight election, Harper’s said he’ll introduce the same budget that got voted down, the opposition says they won’t support it, just like last time, and so the political sphere has decided that unless something changes, David Johnston is going to have to earn his paycheque. Simply put, Harper can’t retain power unless he reaches out, so he has asked for a mandate to not have to reach out.

Who wins the election? We don’t strictly vote for a Prime Minister; by-elections, which are the same thing we’re doing right now, are never construed as a mandate. It’s also not the fact that you can’t be the PM unless you lead the party that wins in an election–BC’s premier isn’t elected at all, but we’re fine with her taking power between elections because the sitting premier resigned, her party has a majority, and therefore the BC Legislature could give confidence to whoever it damn well feels like. What’s clear is that a minority leader must reach across the floor. So if you ask for a mandate to not have to do that, and then you don’t get one, have you lost? On the other hand, if you asked for the mandate to be PM–as everyone but Duceppe has done–and don’t get a minority or a majority, you probably lost for sure. The question becomes, does being a loser make you a loser forever (or until the next election, whichever comes first)? If Harper loses confidence, will everyone just sit in the House and awkardly stare at each other until Johnston just gets mad and sends everyone home for a fifth election in seven years over Christmas? They shouldn’t. That would be dumb.

The whole thing just goes to show that the political system in Canada makes no sense at all. If we elect representatives, then the representatives pick the government. Simple. But some argue that Canadians mean to elect political parties. If that’s the case, that’s screwed up, because spoiler alert: we don’t elect political parties at all. The whole point of the movement of strategic voting–literally voting for someone you don’t believe in because they are more likely to change government–is that people are trying to vote for government, but can’t, because that’s not how our system works. If the point was to elect parties, we ought to be able to vote for them, but we can’t–in the Okanagan-Coquihala and Kelowna-Lake Country ridings, a projected 46,000 votes for the Liberals, NDP, and Greens simply won’t count towards the national total. By comparison, a total of 57,000 votes counts for two. Unifying the vote isn’t good either, because diversity of voting choices rocks. Compared to two-party systems, multi-party scenes allow for a wide variety of viewpoints. Minorities, like the one that brought us universal health care, are awesome, unless they don’t work.

Who’s responsibility is it to make them work? Minority governments haven’t worked for seven years, because they have no rules to appropriately govern them. Because there aren’t any, people have decided that the system is all about political parties, and when the difference gets confusing, people start loudly shouting about what is democratic or undemocratic. Simply put, our system is democratic, but the actual legal workings of our democracy have nothing to do with political parties. It’s like arguing about the spirit of a law–it doesn’t matter what people meant when they wrote it, what matters is what the law says. Do you want to change it? The rest of Canada sure might. The law (or convention, I guess) says that the 308 representatives of the people get to decide whether or not they like government. If you can’t convince them, then I guess you lose.

these photos aren’t mine they’re from the people I said they’re from please don’t sue me. but this post is creative commons so you can pick it up if you want